The Parish Poor

Samuel Hieronymus Grimm, The Soldier's Unwelcome Return. 1776. British Museum, Binyon 7. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Samuel Hieronymus Grimm, The Soldier's Unwelcome Return. 1776. British Museum, Binyon 7. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Introduction

Though there is plenty of evidence about poverty, we know remarkably little about the parish poor of eighteenth-century London: how they got by, and how parish relief fitted into a complex economies of makeshift. No comprehensive parish studies have been completed of the sort that would allow us to determine who among the vast multitude of the poor received a pension, who ended in the workhouse, who was removed as a vagrant, or offered a casual dole in extremis (though two major projects are nearing completion).1 In part, the difficulty lies in the nature of London's ever shifting population. All roads led to London, and a high proportion of London's population was necessarily made up of newcomers and immigrants.2 As a result, we can sample workhouse populations and pension lists, and compare these to population figures; and we can reconstruct the negotiations that took place between paupers and overseers, workhouse masters and beggars, but we cannot provide a precise answer to the question Who were the Poor?

London in 1803

With the rise of more comprehensive parliamentary reporting at the beginning of the nineteenth century, the information available about who the poor were, and how much was spent on them through the parishes at least, becomes more robust. In the 1803 returns, collected in response to An Act for procuring Returns relative to the Expence and Maintenance of the Poor in England, we have a clear end-point to the story of eighteenth-century metropolitan pauperism even if the starting point remains obscure.

These returns paint a distinctive picture which suggests that by the end of the century, London's parishes were uniquely endowed with institutional provision, primarily in the form of workhouses, and that the parishes spent a disproportionate amount on both the "indoor" poor and casual relief, with relatively less spent on pensions and regular outdoor relief than was the case in the rest of England.

Thomas Rowlandson. The Miseries of London. 1807. Lewis Walpole Library, 807.2.1.1. © Lewis Walpole Library.

Thomas Rowlandson. The Miseries of London. 1807. Lewis Walpole Library, 807.2.1.1. © Lewis Walpole Library.

In the year ending in Easter 1803, some £348,988 was expended on the metropolitan poor (including Southwark and a selection of urban parishes beyond the Bills of Mortality). Of this, £219,965 was spent on workhouse care; and £112,236 was spent on outdoor relief. These amounts contributed to housing 14,746 individuals in workhouses, and supporting 11,131 people (above the age of fourteen) as outdoor paupers. A further 10,746 children under the age of fourteen were living with parents or carers who themselves received relief. And 33,187 people were relieved occasionally, or casually. The total number in these different categories, including adults, children and the casual poor comes to 69,810 individuals, out of a recorded population of 864,845 (this figure is taken from the Parliamentary returns, but is certainly too low). This, in turn, suggests that at least 8 per cent of the population of London were in receipt of regular or casual relief.

The same returns also suggest that of this pauper multitude, 16,310 were non-parishioners, and did not have a legal settlement; and that 8,544 were either over the age of sixty or permanently disabled.

The distinctive character of the metropolis is perhaps best reflected in four figures that can be derived from the 1803 returns that illustrate just how different London was to England and Wales as a whole. In London, and of the permanent poor, 57 per cent of paupers were housed in workhouses or their equivalent, while 43 per cent received relief outdoors. In England and Wales as a whole these figures are 20 per cent and 80 per cent respectively. More than this, while 23 per cent of those relieved by London parishes were deemed not to have a settlement, in the country as a whole only 14 per cent of the poor were non-parishioners. And while the metropolitan returns record 47 per cent of individual paupers being casual or in receipt of occasional relief, the figure for England and Wales is only 22 per cent. And finally, the average expenditure in London per individual pauper was approximately £6 12s per person per year; while the figure for England and Wales as a whole was little more than half that figure, at £3 12s.

In other words, metropolitan poverty and poor relief was characterised by the end of the eighteenth century by a remarkably high level of institutionalisation, of relief given to newcomers and migrants, and of support extended to the casual poor in the form of occasional payments. It was expensive, extensive and inclusive.3

Working Backwards

This distinct early nineteenth-century metropolitan pattern can be found at least as far back as the 1720s, when parochial workhouses opened across the capital. By 1776 there were 80 workhouses in the wider metropolitan area, housing 16,100 paupers in institutions, which on average, held 201 individuals each. By comparison, in England and Wales as a whole there were 1,916 institutions housing 90,293 individuals, with an average of 43 inmates per house. In other words, even by 1776, almost 18 per cent of all English and Welsh workhouse inmates lived in metropolitan London, and lived in institutions that were some four times larger than average.4

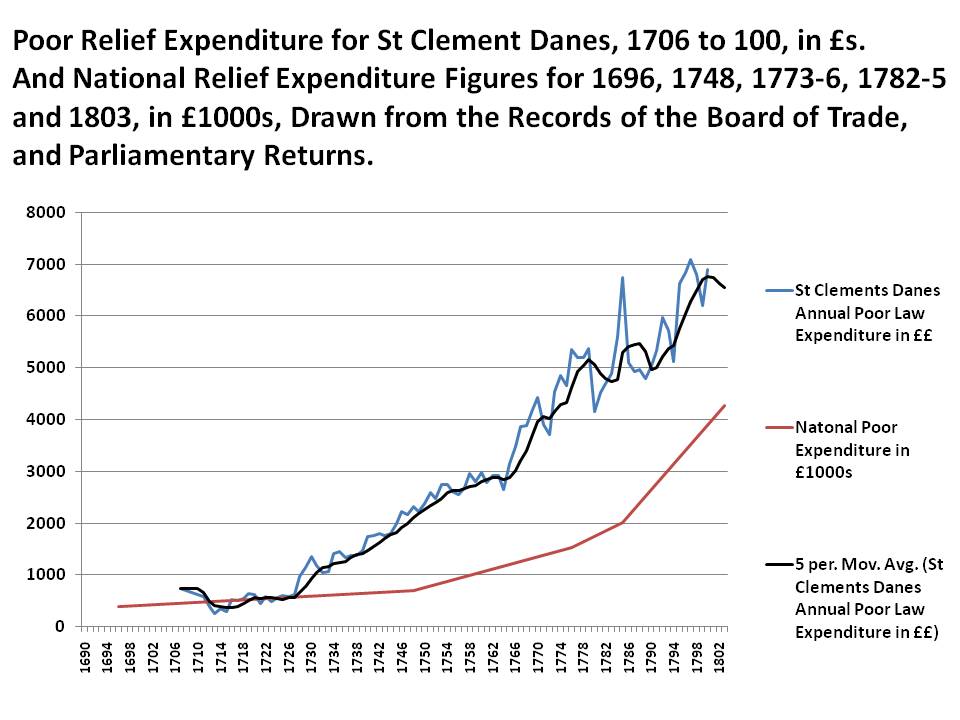

Earlier parliamentary returns and estimates of levels of relief are less satisfactory. But by analysing expenses on the poor for a single parish, we can plausibly examine the extent to which London had a history of providing more comprehensive relief than other parts of the country. The most extensive series of figures we have is for St Clement Danes. This parish did not open a workhouse until 1772, but made wide use of parish nurses. The St Clement material evidences a marked, early and sustained rise in poor expenditure, during a period when the population of the parish was actually falling.

London Metropolitan Archives, St Dionis Backchurch, Churchwarden's Account Books, 1758-1762, 4222/1, LL ref: GLDBAC300070273.

London Metropolitan Archives, St Dionis Backchurch, Churchwarden's Account Books, 1758-1762, 4222/1, LL ref: GLDBAC300070273.

The levels of relief provided in the capital also appear to have been remarkably generous by comparison to non-metropolitan standards. For a thirty year period it is possible to track the level of expenditure on individual paupers in the admittedly wealthy parish of St Dionis Backchurch. Taking both those in receipt of temporary relief and the permanent poor together, the average annual expenditure in the parish per pauper was £5 7s 11d a year, and the most common weekly pension was either 2s or 2s 6d per week. This, however, hides particularly expensive individuals. Charlotte Dionis, for instance, was a foundling who suffered from fits, and was raised from birth to the age of eighteen, when she went to service at parish expense, with a Nurse Collop. The parish spent on average £8 16s per year on Charlotte, and almost £160 in total.

Between 1762 and 1790, St Dionis supported on average just under 80 paupers, out of a population of just under 800 people. Around 10 per cent of the population were in receipt of substantial weekly pensions.5

Gender and Age

Westminster Archives Centre, St Clement Danes, Vestry Minutes, 17th October 1740 - 7th February 1745, B1064, LL ref: WCCDMV362080137.

Westminster Archives Centre, St Clement Danes, Vestry Minutes, 17th October 1740 - 7th February 1745, B1064, LL ref: WCCDMV362080137.

The people who received relief from the parish were most comprehensively characterised by their age (old), gender (female) and physical health (sick). A single page from the annual audit of regular pensioners supported by St Clement Danes reflects this pattern. It is dominated by women and the elderly, and a few families overburdened with children or struck down by injury.

A more comprehensive selection of London's paupers can be found in the workhouse register of St Luke Chelsea, and that for St Martin in the Fields, 1725-1794, both of which are available for browsing and name and keyword searching through this site. The St Luke register, for example, contains details of some 4,342 entries and exits to and from the Chelsea workhouse between 1743 and 1769, and between 1782 and 1799. These figures do not represent individuals, as many paupers entered and left the house on multiple occasions, but they do reflect the overarching character of London's poor. Of the entries into the house, 32% (1,432 entries to the house), involved children sixteen years and younger. 46% (2,015), were adult women, frequently with children in tow; and 21% (925) were adult men.

Among the adults, the average age was just over forty-nine years for men, and forty-one years for women, reflecting a distinctive pattern of poverty whereby women in their twenties and thirties, frequently accompanied by children, had greater access to poor relief (and need of it), than did men in the same age categories. But, more significantly, the figures for both men and women reflect the extent to which it was the elderly who dominated both workhouse populations, and the poor more generally.

Exemplary Lives

Lives using the keywords Casual Pauper:

Lives using the keyword Pauper:

- Ann Somerville, fl. 1790-1796

- Catherine Jones, fl. 1757-1783

- Elizabeth Bridgen, fl. 1750-1773

- Elizabeth Yexley, d. 1769

- George Clegg, fl. 1773-1787

- Isabella Cousins, b. 1765

- John Conway, fl. 1775-1786

- John Simpson, fl. 1748-1754

- Mary Bell, b. 1774

- Mary Broadbent, fl. 1726-1777

- Paul Patrick Kearney, fl.1727-1771

- Rachel Herbert, b. c. 1716

- Repentance Hedges, d. 1730

- Richard Hedges, d. 1716

- Sarah Parker, fl. 1748-1769

Lives using the keywords Pauper Child:

Lives using the keyword Pensioner:

Introductory Reading

- Boulton, Jeremy. "It is extreme necessity that makes me do this": Some "Survival Strategies" of Pauper Households in London's West End During the Early Eighteenth Century. International Review of Social History, Supplement, 8 (2000), pp. 47-70.

- Green, David. Pauper Capital: London and the Poor Law, 1790-1860. Farnham, Surrey, 2010.

- Levene, Alysa. Children, Childhood and the Workhouse: St Marylebone, 1769-1781. London Journal, 33:1 (2008), pp. 41-59.

- Tomkins, Alannah. The Experience of Urban Poverty, 1723-82: Parish, Charity and Credit. Manchester and New York, 2006.

Online Resources

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography.

Footnotes

1 See The Pauper Lives Project for the initial results of a comprehensive study of St Martin in the Fields; and the People in Place project, which is undertaking a reconstruction of both families and property holding in a range of London parishes for the period 1540 to 1710. ⇑

2 The classic statement of the role of migration in the make up of London's population remains E.A. Wrigley, A Simple Model of London's Importance in Changing English Society and Economy, 1650-1750, Past and Present 37 (1967), pp. 44-70 (also in Philip Abrams and E.A. Wrigley, eds, Towns in Societies: Essays in Economic History and Historical Sociology (Cambridge, 1978). For a brief overview of the changing population of London in this period see A Population History of London on the Old Bailey Online. ⇑

3 Parliamentary Papers: House of Commons, XIII, Abstract of the answers and returns made pursuant to Act 43 Geo 3, relative to the expense and maintenance of the poor in England (1803-04). For an excellent analysis of this data see David Green, Pauper Capital: London and the Poor Law, 1790-1860 (Farnham, Surrey, 2010), ch. 1. ⇑

4 Parliamentary Papers: House of Lords, Abstract of returns made pursuant to an act passed in the 16th year of the reign of his majesty King George the Third by the overseers of the poor within the several parishes, townships and places within England and Wales, 1776. For a detailed discussion of the 1776 returns, see Green, Pauper Capital, ch. 2 ⇑

5 For a detailed analysis of poverty in the very different context of the West End, see Jeremy Boulton, The Poor Among the Rich: Paupers and the Parish in the West End, 1600-1724, in Paul Griffiths and Mark S. R. Jenner, eds, Londinopolis: Essays in the Cultural and Social History of Early Modern London (Manchester, 2000), pp. 197-225. ⇑